The Igbo of Nigeria and its religious worship like that of other African societies has been well documented, debated, dramatized and controverted in many respects beginning with the missionary and colonial encounters. Eact time I read or try to make sense of Igbo worship, I seem to pinch myself given the way in which religious pundits portary ancestor worship in Africa, particularly Igbo society. What is worshippingg God or Chukwu for the Igbo? How do the Igbo celebrate chukwu in worship? I have culled the following article from www.kwenu.com where I first attempted to relate Igbo chukwu worship as something we need to rethink.

The Igbo of Nigeria and its religious worship like that of other African societies has been well documented, debated, dramatized and controverted in many respects beginning with the missionary and colonial encounters. Eact time I read or try to make sense of Igbo worship, I seem to pinch myself given the way in which religious pundits portary ancestor worship in Africa, particularly Igbo society. What is worshippingg God or Chukwu for the Igbo? How do the Igbo celebrate chukwu in worship? I have culled the following article from www.kwenu.com where I first attempted to relate Igbo chukwu worship as something we need to rethink.

I begin this submission by asking the following questions: at what types of situation and for what purposes do the Igbo worship Chukwu, God, or pray and with what symbols of their cultural spirit and heritage? Why can’t Igbo religious experts come out bold and tell us that Igbo religion is, and can best be called, Igbo Chukwu Worship and is simply one and the same thing as any other like Christianity? Christianity we understand is a religion named after Christ, the ‘Son God,’ and therefore it represents the followers of Christ just like the Igbo are the followers of Chukwu, God; thus, ‘Community God.’

Continuing to categorize and write about the Igbo Chukwu Worship as it was long written down in missionary history in Africa and transmitted by the missionaries and colonialists as ‘Ancestor Worship’ is but a marginal frame of the deep-seated semantics and significance of Igbo religious expansive cultural lifestyle, change, and continuity. Times have changed for a new description of what Igbo worship needs to refer to – experientially, symbolically, thoughtfully, and pragmatically. I make bold to call for a new pragmatic reflection – and let us call our religion what we know it for – hence Igbo Chukwu Worship, not Igbo Ancestor worship which connotes colonial subjectivity.

Referring to the ancestor by the Igbo when in a prayer session or incantation moment was misunderstood by the missionary-colonial authorities to mean worshiping the dead ancestors. The Igbo do not worship the dead ancestors; rather they call up the virtues of known ancestral forces that constitute part of their cosmology of life and world. Ancestors are not called up without Chukwu, Obasi di n’elu (the almighty God above). In other words, ancestors are just a frame of their descent relationship and of kinship alliances in the making of their thought and reality meaningful. The actual worship is rooted to God, Chukwu the biggest being they can imagine, experience, refer to, call upon, submit to, and know well and are passionate about. Praying to Chukwu for the Igbo and by the Igbo is an act of empowerment and psychological survival pattern of life that is so much culturally endured. Chukwu or Chi is a language of everyday life renewal with and hope in God. And the zeal and passion with which the Igbo govern their lives, culture, and society with “Chukwu Worship” need not be undermined with the colonial notion of ancestor worship ascribed to the Igbo in particular and Africa as a whole.

As Katharine Slattery equally notes:

“There is a strong Igbo belief that the spirits of one’s ancestors keep a constant watch over you. The living show appreciation for the dead and pray to them for future well being. It is against tribal law to speak badly of a spirit. Those ancestors who lived well, died in socially approved ways, and were given correct burial rites, live in one of the worlds of the dead, which mirror the worlds of the living. They are periodically reincarnated among the living and are given the name ndiichie – the returners. Those who died bad deaths and lack correct burial rites cannot return to the world of the living, or enter that of the dead. They wander homeless, expressing their grief by causing harm among the living.” (When identified as troubling will be tied up in sacrifice of last resting).

Further, Katharine Slattery accounts with some modification here that:

Religion was regarded with great seriousness, and this can be seen in their attitudes to sacrifices, which were not of the token kind. Religious taboos, especially those surrounding priests and titled men, involved a great deal of asceticism. The Igbo expected in their prayers and sacrifices, blessings such as long, healthy, and prosperous lives, and especially children, who were considered the greatest blessing of all. The desire to offer the most precious sacrifice of all led to human sacrifice …, as even Christ was for repentance, remission, change and continuity? – in order to provide a retinue for the dead man in life to come. There was no shrine in form of Temple or Cathedral to Chukwu, but there was one symbolized in every family regarded as Chi. Sacrifices were made directly to Chi, but Chukwu was conceived as the ultimate receiver of all sacrifices made to the minor deities. {italics in citation are mine}.

We can argue up to any length on this call, but the bottom line is that the Igbo of Nigeria worship Chukwu and deserve to have their religious life correctly identified and labeled on their own cultural terms and realities. This is even more important now the Igbo have become an inevitable global migration story and the opportunities, challenges, and braves in which living with the ‘other’ provides in a challenging world.

This essay is primarily offered to show the significance of Igbo Chukwu worship in a culture of diversity. As the Igbo Cultural Association of Calgary celebrates Igbo Day, 2010; it becomes obvious to reflect on how colonialism and missionalism helped Igbo religious worship to embrace change and continuity. Around Calgary and other regions in Canada, new titled churches led by the Igbo are emerging and helping the Igbo spirit and religiosity in many ways. In a changing world, the Igbo have shown resilience, industry, perseverance, political reunion, economic adaptation, religious energy, and hope in pursuit of identity and kinship as a group.

The essay draws from the work of Prof. Emmanuel Onwu’s article “Igbo Traditional Religion and Christianity” (March, 2009). It also brings out a personal interpretation being a complementary perspective with respect to diversity, culture change, and adaptation. Onwu’s work which draws from Chinua Achebe’s novel, Things Fall Apart (1958), outlines Igbo religion and Christianity in order to understand them. We follow the same context to examine cultural heritage, while taking note that each of the religions – Igbo Chukwu worship and Christianity – is a cultural paradigm of worshipping the supreme God, or Chukwu in Igbo parlance; and that encounters between cultures are necessarily bound to create both continuity and change. The essence of the submission is therefore to give insight on the meaning and dynamics of the things that hold a culture together and how those things play out in re-mobilizing and moving on in a time of critical need by a group. It calls for how we can transmit the values of culture change and continuity through Igbo Cultural Day celebrations in Calgary and elsewhere.

According to Onwu, Achebe gives a written description of the impact of the encounter between Igbo indigenous religion and Christianity when Obierika says: “How do you think we can fight when our own brothers have turned against us? White man, oyibo, is agbara, is very clever. He came quietly and peacefully with his religion for ritual emancipation on his “human rights lips” and his “diplomatic, economic, and political bag” at his back for business. We were amused at his foolishness and allowed him to stay. Now he has won our brothers and our clan can no longer act like one. He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart” (1958: 123-125).

In 2005, I argued elsewhere that Achebe’s uses of the words “knife” and “things” that held us together be viewed not in the literal sense, but as deeply symbolic, metaphoric comments on the meaning of Igbo culture, community, logic of the other, and worship. Thus, Achebe asserts here that the Igbo culture and sense of solidarity and communalism (“things”) were punctured by a new cultural force they were not prepared to take seriously or engage with. Thus, “falling apart” means to withdraw and recoup prior to returning and belonging. Prof. Pantaleon Iroegbu once took a similar philosophical and theological view when he advanced that Igbo philosophy and metaphysics are all about belongingness, being qua being, existentialism, adaptation, and survival. In his the Kpim of Personality: Treatise on the Human Person (2000:125-126), he further illustrated this as ‘relational liberty’ which he called okeakwalam – a liberty of belongingness for all and argues that the promotion of one is the promotion of others and vice versa. Igbo Chukwu worship espouses this.

With Chukwu, the Igbo affirm that “onye kwe, chi ya ekwe” (when someone agrees, his god agrees too). The change brought about due to the missionary confrontation to open the Igbo up to other cultural realities of worshiping God was not meant for one person who needed it the most but for all Igbo at that historical moment of colonial cultural encounter. We need to see that in Things Fall Apart, the Igbo were recreated (chi ekegherie ha) through the most needy adherents so they could face the new world. As they say, “seeing is in believing”; the Igbo of that moment saw and believed in the changing dimensions of their powerful culture. It is in this way that the Igbo of Nigeria enjoy migration as a means of discovering and being discovered through cultural hospitality, learning and acquiring skills, and gathering experiences that result in development at home and wherever they may sojourn. Thus, “things fall apart,” can be interpreted as an account of a historic moment of intercultural change, adaptation, and continuity.

We celebrate Igbo culture for many reasons, including the representation of Igbo Chukwu worship. Kolanut is still used to pray reverently to Chukwu, and it is still divinized and given the aura of God, peace, and hospitality as we share life, knowledge, and resources with our neighbours. We also pray with palmwine to bless the good and curse the evil. Throughout Africa and in Diaspora, the Igbo are mainly devout Christians who take worship so seriously that their neighbours often wonder how they can combine their zeal for entrepreneurship with their religiosity. So, in describing the cultural encounter in Things Fall Apart as a puncturing of the things that held the Igbo together, Achebe was prophetic in capturing the re-creation—both through change and continuity—of a society through the power of cultural contact. In the sharing of cultural knowledge and strategies for success, development expands when cultures interact and blend. When the Igbo worship Chukwu in their own terms, Christianity does not do otherwise on the contrary. Rather, the trouble with cultural encounters is that they force one and another into a new set of relationships for adjustments called change, a change that will become inevitable due to need by the followers.

In his writing on traditional Igbo religion, Prof. Emmanuel Onwu tells us that Achebe’s words echo the sentiments expressed by an Igbo elder as he reflected on how the new religion of Christianity evolved in terms of winning converts, dividing members of the clan, and helping the Igbo acquire new life, knowledge, and intercultural sensitivity. It is certainly true that, from the moment of experiencing the new culture, things would never be the same for the Igbo. And this is so because, in reality, there is no such thing as a “fixed” culture—no culture, no matter how long standing, will remain the same upon encounter with another. So does foreign religion divide or unite? And how exactly did the missionary manage to win some of the Igbo over to Christianity?

Achebe points out that Nneka wasted no time joining the Christian church when she became pregnant because she had been losing her children through ogbanje (a repeating spirit phenomenon). And outcasts in Mbanta flocked the church in pursuit of freedom from evil spirits and oppression. Also, there were the cases of Nwoye, who was shocked when twins were “thrown away” in the forest to die, and Ikemefuna, who was killed for sacrifice by his father, Okonkwo. Onwu also reminds us that, when the Igbo of the time gave over the evil forests and shrines of their various gods to Christian missionaries, nothing happened, contrary to common expectations. And, while the Igbo hung on to those failed shrines and gods and did not completely imbibe Christianity, the perception was that those gods were dead (but were they?), and the people became convinced that the white man’s God was very powerful. The priestess of Agbala in Umuofia spitefully called the Christians the excrement of the clan and the ‘new faith’ a mad dog that had come to eat it up (Achebe, 1958:101). And, indeed, religion migrates in these circumstances and liberates, that is “eats up” or feeds the most needy, producing both change and continuity.

Achebe points out that Nneka wasted no time joining the Christian church when she became pregnant because she had been losing her children through ogbanje (a repeating spirit phenomenon). And outcasts in Mbanta flocked the church in pursuit of freedom from evil spirits and oppression. Also, there were the cases of Nwoye, who was shocked when twins were “thrown away” in the forest to die, and Ikemefuna, who was killed for sacrifice by his father, Okonkwo. Onwu also reminds us that, when the Igbo of the time gave over the evil forests and shrines of their various gods to Christian missionaries, nothing happened, contrary to common expectations. And, while the Igbo hung on to those failed shrines and gods and did not completely imbibe Christianity, the perception was that those gods were dead (but were they?), and the people became convinced that the white man’s God was very powerful. The priestess of Agbala in Umuofia spitefully called the Christians the excrement of the clan and the ‘new faith’ a mad dog that had come to eat it up (Achebe, 1958:101). And, indeed, religion migrates in these circumstances and liberates, that is “eats up” or feeds the most needy, producing both change and continuity.

At the base of Igbo culture, when the colonists and missionaries wanted the Igbo to surrender their children for education, the Igbo chiefs refused for fear of mortifying their heritage of Igboness. But the Igbo no longer make noise about colonial incursions because they have embraced the change it offered as an opportunity to expand their cultural values and horizons. This does not mean they did not resist—in fact, they did so much longer than any other group in Africa with the exception of the Zulu. The point is, however, that, as soon as the Igbo discovered the benefits of changing taboos via new religious belief and migration, they embraced it as useful change and heritage. There is no wonder that, both in Nigeria and around the world, the Igbo have proven to be shrewdly adaptable and present with a high religious and cultural spirit.

The advent of Christianity in Igboland meant the introduction of a Christian worldview. And Christianity was inherited as a form of achievement that “abolished slave trade and slavery, human sacrifices and twin killing, introduced education, built hospitals and charity homes” (Onwu 2005). Furthermore, Christianity decreased superstition and increased knowledge that brought about improved human welfare and reshaped the Igbo’s faith and worldview. Nevertheless, Igbo indigenous religion is still alive, a heritage we cannot ignore. The Igbo call on Chukwu everyday – as they eat, play, work, pray, face childbirth, illness, challenges, and even as they make love!

The early missionaries saw themselves as social and religious reformers whose aim was to condemn African religious and social beliefs and practices and replace them with their own. But, where they had hoped to produce a “new person” born into a new faith, what actually happened is that the “new person” became a split personality—one who could neither totally return to the old nor become firmly rooted in the new. As such, the Igbo continue to seek the African face of God in the Chukwu they know, love, and worship. The English language sound of “God” is not as moving as the Igbo language tone of “Chukwu.” Think it about!

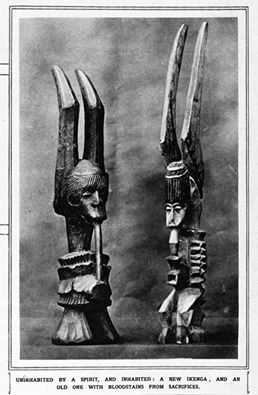

One Igbo in Achebe’s Things Fall Apart asks the missionary this: “If we leave our gods and follow your god, who will protect us from the anger of our Chi – our dumped god?” In response, the missionary angrily says: “Your gods are not alive and cannot do you any harm. They are pieces of wood and stone.” Are they? There is a misinterpretation, in other words, some ethnocentric feeling here. The Igbo know well that deities and spirit forces are part of their everyday lives. Igbo Christianity combines local forces, ecological and ancestor resources to seek solutions and find protection in the face of need. This is considered cultural and a responsibility. The Igbo fought against the European missionary intrusion, discovered it was inevitable, and embraced the culture shock. But images of Chukwu and God are woven into the common symbols of a culture, and the Igbo continue to showcase enduring worship or ritual symbols such as ofo, ogu, agwu and ikenga. Let us face it, Igbo worship is strong and a heritage of life and spirit of powerful relationship with God, Chukwu.

One Igbo in Achebe’s Things Fall Apart asks the missionary this: “If we leave our gods and follow your god, who will protect us from the anger of our Chi – our dumped god?” In response, the missionary angrily says: “Your gods are not alive and cannot do you any harm. They are pieces of wood and stone.” Are they? There is a misinterpretation, in other words, some ethnocentric feeling here. The Igbo know well that deities and spirit forces are part of their everyday lives. Igbo Christianity combines local forces, ecological and ancestor resources to seek solutions and find protection in the face of need. This is considered cultural and a responsibility. The Igbo fought against the European missionary intrusion, discovered it was inevitable, and embraced the culture shock. But images of Chukwu and God are woven into the common symbols of a culture, and the Igbo continue to showcase enduring worship or ritual symbols such as ofo, ogu, agwu and ikenga. Let us face it, Igbo worship is strong and a heritage of life and spirit of powerful relationship with God, Chukwu.

To conclude, it is worth examining this question: are cultures equal? Has Christianity more culture than traditional Igbo Chukwu worship? From the point of view of culture theory and application, all cultures are equal but different. A society such as the Igbo upholds a culture for its ability and capacity to respond to their needs. Therefore, a religion is equal to every other as long as it renders to the users what they consider important in managing their ethical universe. The Christian Cultural Science that views Christianity as superior to Igbo Chukwu religion is erroneous. In healing, a healer looks to and embraces forces and resources that provide what is needed—so it is with religion. That is the essence of migration, diffusion, and adaptation. Instances drawn from Achebe’s Things Fall Apart exemplify this. What experts need to do is to reposition the concept of change and diversity as a means by which the Igbo embraced the expansion and change that resulted in a coalescing of Christianity and traditional religion. Diversity is all there to understanding the Igbo and their system of worship in their challenged and changing world for inclusion, opportunity, and security. The considered values of a culture are not only captured in terms used but also in the transmission of the change that follows through worship and celebration. Nwachukwu and Nwagbara are names in Igbo of the same identity of person in God and Chukwu in Igbo thought and reality.

Selected References Consulted

Chinua Achebe, 1958. London: Heinemann.

Katharine Slattery, August, 15, 2001. “Religion and the Igbo People”. Imperial Archive Project. In Odinani, www.kwenu.com. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

Onwu, Nlenanya, Emmanuel, 2009 & 2010. “Igbo Traditional Religion and Christianity”. Retrieved June 5, 2010. Codwit News: http://www.codewit.com/igbo…/igbo-traditional-religion-and-christianity.html

Pantaleon Iroegbu, 2000. Kpim of Personality: Treatise on the Human Person. Owerri, Nigeria: Eustel Publications.

Pantaleon Iroegbu, 1995. Metaphysics: The Kpim of Philosophy. Owerri, Nigeria: International Universities Press Ltd.

Patrick Iroegbu, 2010. Introduction to Igbo Medicine and Culture in Nigeria. Indiana, USA: Lulu Publishing Enterprises (www.lulu.com)

Buti Tlhagale, 2010. “Bringing the African Culture into the Church”. Retrieved August 4, 2010. In Odinani – www.kwenu.com.

……………………………………………………………………………………….

Note

Elsewhere, an abridged two-page copy of this essay/speech was presented in the event brochure of Igbo Day 2010 of the Igbo Cultural Association of Calgary, Canada (ICAC). The event was overwhelmingly attended and participants were heavily entertained with rich Igbo cultural kolanut ceremony, Igbo kwenu lifestyle, speeches, appreciations, awards, dance performances – men, women, children, including the exciting Bende War Dance Troupe, led by Don Odoemenam. Huge fashion display, rich Igbo cuisine and new yam festival all blended with the awesome occasion. To my own estimation, over 800 people were in attendance for the celebration of the rich cultural heritage of the Igbo people of Nigeria held on Saturday, August 14, 2010 at Thorncliff Community Center, 5600, Centre Street North, Calgary, Alberta Canada. I hope by reading this piece you will appreciate the critical insight Igbo Chukwu Worship can be to a celebrating community of their Igbo Day, 2010. Congrats to ICAC on a successful Igbo Day and New Yam Festival outing in a complex global city.

Inside the City of Oldenburg,Hey ,How are you?fine,Can you use my camera and make some photos for me ?yes ,for sure,That is great from you thanks,

Inside the City of Oldenburg,Hey ,How are you?fine,Can you use my camera and make some photos for me ?yes ,for sure,That is great from you thanks, If you dont mind you can join me ?,lol for sure,peace and love to the City and the people of Oldenburg,

If you dont mind you can join me ?,lol for sure,peace and love to the City and the people of Oldenburg,

It is nice beign to the City Festival,every one was so happy walking,dancing,eating and drinking,

It is nice beign to the City Festival,every one was so happy walking,dancing,eating and drinking,

The Igbo of Nigeria and its religious worship like that of other African societies has been well documented, debated, dramatized and controverted in many respects beginning with the missionary and colonial encounters. Eact time I read or try to make sense of Igbo worship, I seem to pinch myself given the way in which religious pundits portary ancestor worship in Africa, particularly Igbo society. What is worshippingg God or Chukwu for the Igbo? How do the Igbo celebrate chukwu in worship? I have culled the following article from

The Igbo of Nigeria and its religious worship like that of other African societies has been well documented, debated, dramatized and controverted in many respects beginning with the missionary and colonial encounters. Eact time I read or try to make sense of Igbo worship, I seem to pinch myself given the way in which religious pundits portary ancestor worship in Africa, particularly Igbo society. What is worshippingg God or Chukwu for the Igbo? How do the Igbo celebrate chukwu in worship? I have culled the following article from

Achebe points out that Nneka wasted no time joining the Christian church when she became pregnant because she had been losing her children through ogbanje (a repeating spirit phenomenon). And outcasts in Mbanta flocked the church in pursuit of freedom from evil spirits and oppression. Also, there were the cases of Nwoye, who was shocked when twins were “thrown away” in the forest to die, and Ikemefuna, who was killed for sacrifice by his father, Okonkwo. Onwu also reminds us that, when the Igbo of the time gave over the evil forests and shrines of their various gods to Christian missionaries, nothing happened, contrary to common expectations. And, while the Igbo hung on to those failed shrines and gods and did not completely imbibe Christianity, the perception was that those gods were dead (but were they?), and the people became convinced that the white man’s God was very powerful. The priestess of Agbala in Umuofia spitefully called the Christians the excrement of the clan and the ‘new faith’ a mad dog that had come to eat it up (Achebe, 1958:101). And, indeed, religion migrates in these circumstances and liberates, that is “eats up” or feeds the most needy, producing both change and continuity.

Achebe points out that Nneka wasted no time joining the Christian church when she became pregnant because she had been losing her children through ogbanje (a repeating spirit phenomenon). And outcasts in Mbanta flocked the church in pursuit of freedom from evil spirits and oppression. Also, there were the cases of Nwoye, who was shocked when twins were “thrown away” in the forest to die, and Ikemefuna, who was killed for sacrifice by his father, Okonkwo. Onwu also reminds us that, when the Igbo of the time gave over the evil forests and shrines of their various gods to Christian missionaries, nothing happened, contrary to common expectations. And, while the Igbo hung on to those failed shrines and gods and did not completely imbibe Christianity, the perception was that those gods were dead (but were they?), and the people became convinced that the white man’s God was very powerful. The priestess of Agbala in Umuofia spitefully called the Christians the excrement of the clan and the ‘new faith’ a mad dog that had come to eat it up (Achebe, 1958:101). And, indeed, religion migrates in these circumstances and liberates, that is “eats up” or feeds the most needy, producing both change and continuity.

August September October,November and December is the Time of Igbo Celebrations,Culture and Tradition,Omenana Igbo na Odinana Igbo,very very Important to every Igbo Children,home and in Diaspora,

August September October,November and December is the Time of Igbo Celebrations,Culture and Tradition,Omenana Igbo na Odinana Igbo,very very Important to every Igbo Children,home and in Diaspora, The time Igbo Masqurades Dance with Igbo people,signs of peace between the living and the spirits of Igbo Land,because Igbo people believe that masqurades repressents the spirits of Forefathers,and they are always invited,

The time Igbo Masqurades Dance with Igbo people,signs of peace between the living and the spirits of Igbo Land,because Igbo people believe that masqurades repressents the spirits of Forefathers,and they are always invited, It is lovely because everyone must be happy,as people dance till they get tired,lol,

It is lovely because everyone must be happy,as people dance till they get tired,lol, New Yam festival,first fruits of the year,in August many region in Igboland celebrates this,like Nnewi,Nri,Imo,Abia,Rivers,Calabar etc,many BIafrans ,Visit Igboland in This time of August and withness the nature Culture and tradition of Ancient Israelites,those who still live in NIgeria.

New Yam festival,first fruits of the year,in August many region in Igboland celebrates this,like Nnewi,Nri,Imo,Abia,Rivers,Calabar etc,many BIafrans ,Visit Igboland in This time of August and withness the nature Culture and tradition of Ancient Israelites,those who still live in NIgeria. Jews Identity Among The Igbo of Nigeria,this book will let you to understand many things about the Igbo Culture and Tradition,and when every one been celebrated,you can get a copy from amazon,

Jews Identity Among The Igbo of Nigeria,this book will let you to understand many things about the Igbo Culture and Tradition,and when every one been celebrated,you can get a copy from amazon, When read much books about the Igbos you will like the Igbos the more you knows about them,because they are lovely people,you can contact Remy Ilona the writer of many books about the Igbos and the Jews,

When read much books about the Igbos you will like the Igbos the more you knows about them,because they are lovely people,you can contact Remy Ilona the writer of many books about the Igbos and the Jews, Igbo Amaka ,like and share.

Igbo Amaka ,like and share.